What to Expect from your Teaching Induction

I’m Carl, a second year PhD student at the University of Nottingham and I’ll be blogging about my initial forays into teaching History. My own thesis is a reappraisal of the Paulician heresy and my broader interests focus on Byzantine religious and intellectual history, so my research is about as niche as it’s possible to get! I’ve been thinking about teaching for much of the past year, but the fact that it is now upon me has come as a shock to the system. For the last few years my research has been funnelled into increasingly specialist fields and suddenly I’m being asked to broaden my scope to cover a thousand years of medieval history. In a way it feels like turning the clock back, particularly since I’ll be teaching one of the courses I took myself five years ago.

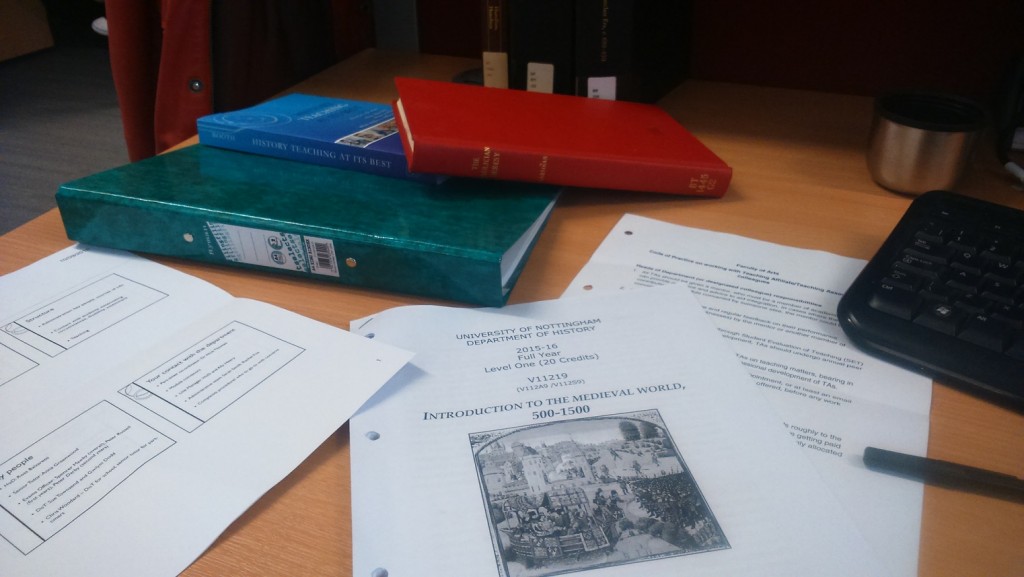

By now, I’ve attended the relevant inductions and training courses and have nothing left to do but begin. The training that I’ve done so far has proved helpful, even if it wasn’t exactly what I expected. One thing that is immediately apparent and was stressed to us at our departmental induction is the importance of teaching to the department’s ethos here at Nottingham. It’s clear that a major overhaul has been conducted in the last few years, bringing about a number of changes since my own days as an undergraduate. The department is making more of an effort to ensure that students are aware of the department’s aims and methods. Personally, I’ve found this approach very helpful, since it has allowed me to place my own teaching in the wider context of the department and the university as a whole. I’ve actually caught myself thinking about why ‘we’ teach in the way that ‘we’ do, which is a refreshing change from being preoccupied with myself. I’ve also spent a lot more time thinking about students rather than myself, which makes things far less intimidating.

But how am I going to teach?

This is something that we have had surprisingly little guidance about, save for a useful session on ‘small group teaching’ which gave advice on tackling common problems in seminar groups. From the outset, the matter of how I should teach has preoccupied me, since I’m not really a typical History PhD (but then who is?). I began university as a mature student who never studied History at GCSE or A Level, so I initially thought that my experience of studying the subject would be completely different from that of the students I’ll be teaching. My main concern was that I would struggle to have reasonable expectations of my students, because I have little idea of what has been expected of them previously. But it has since become clear that all departments struggle with similar issues, given the changes that have been imposed on the education system in recent years. The widening gap in what’s expected of A-Level versus university students is an increasingly significant problem and one that was discussed thoroughly in the induction.

Training

Although our induction focused on theory rather than the practicalities of teaching, all PhD students have been exposed to a variety of teaching styles and have a good idea of what works and what doesn’t. Even before I’ve begun, it is apparent that teaching is a very individual thing that simply can’t be taught. It takes time and experience to put that accumulated knowledge into practice and develop your own teaching style. This is where the departmental community really comes in helpful. I’ve already received kind offers of help from staff and fellow postgraduates, which I’ll no doubt draw upon in the future. I’ll also read a few more articles and go through the videos on this site again. But the thing I expect to draw on most is my own experience. I had virtually no knowledge of medieval history prior to taking this course as an undergraduate. In that sense, I can empathise with my students a good deal and I hope to transmit some of the reasons why I’m still studying this fascinating discipline five years later. Of course I’ll make some mistakes in the meantime – and knowing me I’ll make more than I really need to – but hopefully by sharing these with other new tutors I’ll help them avoid similar pitfalls.

Your blog raises so many issues about starting to teach that I can’t begin to address them all here. But, even though it was a long time ago, it really brought back my own feelings when I started teaching a year into my PhD. The only difference is that back in the day there was no induction in teaching with all the additional terror that brought; so things are definitely better now.

I remember the same, slightly disorientating, sense of going from an increasingly narrow research focus to a very general teaching one. This was a bit scary but actually it really helped my thesis – made me put it into a much bigger chronological/historiographical picture I was in danger of forgetting in my obsessive focus on the primary sources.

I also want to point out the importance of feeling part of your Department and emphasize how willing people are to help you – something you raise but I never really appreciated at the time. I remember feeling a bit isolated as a postgrad and, as our UK survey showed, most historians can remember similar feelings and this means they will be ready to help. Never hesitate to ask for advice – as the films on the site demonstrate.

Finally, you’re right – you ‘will’ make mistakes and that’s both inevitable and a good thing (for everyone who teaches, no matter the extent of their experience). Teaching history is something you can never be perfect at (thank goodness); it’s about keeping trying things out – not least because each class is different and so will you be. Draw on your experience and passion for the subject – but also remember your students are not necessarily like you!

Interesting blog. I can confirm what Alan said that training in the past was non-existent (literally). My first teaching experience, some 27 years ago, was, like yours, teaching a general medieval survey course. I had no training at all (really), but it was to four students which made it easier to administer at least! Three of them got firsts in the end, so something must have gone right.

All these years later I still find teaching those big survey modules a challenge, as trying to get students to think big is hard given that most of their education (and ours) tells us to think small (specialist). Being aware of that, as you are, is a really good starting point.

One thing I always do is to check regularly with them as a group about how what they are doing relates to their previous experience of studying history: however different that may have been it is always good to reflect on learning processes, getting them to realise that learning is about what they do not what is done to them.

I’ve also used a quiz at the end of the term to get them to recap what they have learned and to realise how far they have come in few short weeks from where they started. They usually get everything right too!

As the person who delivered that teaching induction this is a very useful insight, especially the things which have come as a surprise or have stressed people out. I’m certainly well aware of a need for us to discuss what we’re trying to achieve in teaching, hence the emphasis on this in the opening session.

As to the question of guidance on how to teach, I think the comments from Alan and Ross are reassuring. There is no ‘correct’ approach and all of us are continuing to develop, reflect, etc, in this area, especially in light of the many changes we are facing. This assumption will inform the ongoing training sessions will I’ll run – I can propose possibilities and I can get people thinking, but then it’s up to individual teachers to try different things. On the one hand that’s quite scary, but it’s also quite energizing and liberating.

Thanks Carl for such an interesting (and honest) blog entry. I hope those first classes go well!

I certainly recall sharing many of your sentiments about teaching large survey courses when I started out. However, as Alan says there is much to be gained from teaching such courses. They encourage you to reflect regularly on the broader implications of your own research; they offer rewards – such as seeing your first-years begin to think “big” about historical change for the first time – that teaching your own specialism does not; and they take you out of your comfort zone, often to a place where you can come up with your most creative and innovative strategies for teaching (free of the constraints of detailed, specialist knowledge!).

Your point about our lack of knowledge of the “gap” between the A-level system and university history teaching is an excellent one. I am currently doing some work with A-level teachers and the School of Education’s History subject interest group about bridging that gap, and it is a significant challenge both for us and for schools. We do need to do more to explore and understand the differences between the two approaches, perhaps by asking our students some of the questions Ross mentioned, but also perhaps by discussing openly with students from the outset both their expectations of history teaching at university and our expectations of them as university students. I often do this at the start of a Year 1, 2 or 3 module and then return to these issues at the module’s close. You may find yourself faced initially with a lot of ‘WTF?’-type expressions, but the rewards, especially in terms of building a shared learning environment with your students, are often well worth it.

Finally, I can’t echo enough the other respondents’ – and your own – points about seeking out advice wherever possible. Don’t be afraid to ask convenors and other tutors for advice; take up opportunities for observation – both of your own and others’ teaching – wherever possible; keep in mind the ethos and aims of the department. And of course, draw upon your own experiences of good (and bad) teaching too – that is an invaluable resource that no teacher training can replicate!

I’ve now taught a few classes and thought it would be a useful idea to revisit this blog to see how my thinking has changed in a few short weeks, not least due to the insightful comments above, which I’ll address to some extent here. The first thing that strikes me is how quickly your thinking develops at this early stage of a teaching career. There are already a few anxieties in the original blog I can confidently say I’ve addressed, even if a few other challenges have cropped up. I’m now certain that my background hasn’t proved as much of a handicap as I initially feared. I’m also aware that teaching isn’t nearly as difficult as I thought it would be in terms of expressing myself to my students. That being said, I still have a lot to learn, especially in terms of making the material accessible while still challenging the students. It’s a difficult balancing act.

One of my reservations at the outset of the course was that I thought I would find it difficult to teach, since the module spans a full millennium. But I can already understand the logic of exposing PhD students to history teaching through these survey modules: it really forces you to think about every aspect of how you teach and go about enthusing your students. Since your preparation is often only one week ahead of your students you can also put changes into practice immediately, depending on which activities go well and which don’t. So it’s certainly a good way to learn as you go and in retrospect I think teaching something that isn’t your own specialism actually helps. The modules are also broad enough that you can take a few risks in your classes, as Nick and Joe have noted above. This is something I’m planning on doing in a couple of upcoming classes and I’m surprisingly confident about it (at least at the moment!)

The importance of the departmental community, which most of the comments have addressed, still stands. I’ve only taught two classes to date and the issues that I identified with those classes were easily addressed by a few helpful conversations from friends and colleagues. It can be something as simple as where to stand while talking to a group, or how to get students to offer their own opinions freely without feeling pressured. Having someone who can offer a solution from their own experience is so much easier than trial and error. It really is a tremendously important resource to a new teacher and it’s something I’d encourage newcomers to make use of at every opportunity. Even if your questions seem obvious or a bit trivial you’ll save yourself a lot of time and effort in the long run.

Many thanks for these thoughts Carl. As you’ve worked out, its far easier to train a new teacher how to deal with specific issues when something goes wrong, than it is to teach them how to teach in the first place! I think this is why all of us who have gone on those training courses find them a little frustrating. But the sort of reflexivity that this blog encourages is a good tool in this respect, because it makes us think about our own practice as being just as important as a starting point in a class as is the students’ own preparation and contribution.